“…a wife, that most interesting specimen in the whole series of vertebrate animals…” -Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin had a lot to say about love—and not just in The Origin of Species. While he was off devising one of the most famous scientific theories in history, he was simultaneously engaging in a romance that defied all of his own logic.

Darwin was in many ways the quintessential scientist, proposing a theory of the world (evolution) that flew in the face of traditional religion. Emma Wedgwood, meanwhile, was devoutly religious and concerned over Darwin’s godlessness. (She was also his first cousin. Didn’t Darwin ever study genetic variety?)

But the strength of Emma and Darwin’s relationship proves that love can survive despite all odds – even when two people can’t agree on any of the world’s most fundamental truths.

The Courtship

Darwin—an orderly, logical man—had always treated romance with a stark lack of sentimentality. Before meeting Emma, he devised a “pro/con” list for marriage, carefully weighing the costs and benefits of a union.

Under ‘marry’ he wrote the following endearments:

1.) Constant companion

2.) Better than a dog anyhow

Under “don’t marry,” he wrote:

1.) Conversation with clever men at clubs

Here’s a general piece of advice: if you’re debating between a dog and a spouse, be kind to yourself and your spouse—go with the dog. But Darwin managed to change his mind—and rather dramatically—once he met the right person. A letter to Emma in 1829 reflects his changing conception of marriage:

I think you will humanize me, and soon teach me there is greater happiness than building theories and accumulating facts in silence and solitude.”

A surprising statement from the man who once said: “A scientific man ought to have no wishes, no affections—a mere heart of stone.”

Good work, Emma.

Opposites Attract?

One believed in apes, one believed in God. It would appear to be an insurmountable barrier, especially since the differences in their opinions only grew more pronounced. Darwin became increasingly agnostic, and Emma became increasingly concerned:

May not the habit in scientific pursuits of believing nothing till it is proved, influence your mind too much in other things which cannot be proved in the same way, & which if true are likely to be above our comprehension.“

Darwin wrote her back, at bottom of the letter:

When I am dead, know that many times, I have kissed & cryed over this. C. D.

Out of their arguments grew a healthy respect for the other’s opinion—and so, Charles and Emma managed to transform their greatest difference into their greatest source of strength. They developed an unlikely bond, one which depended on open communication and spirited debate.

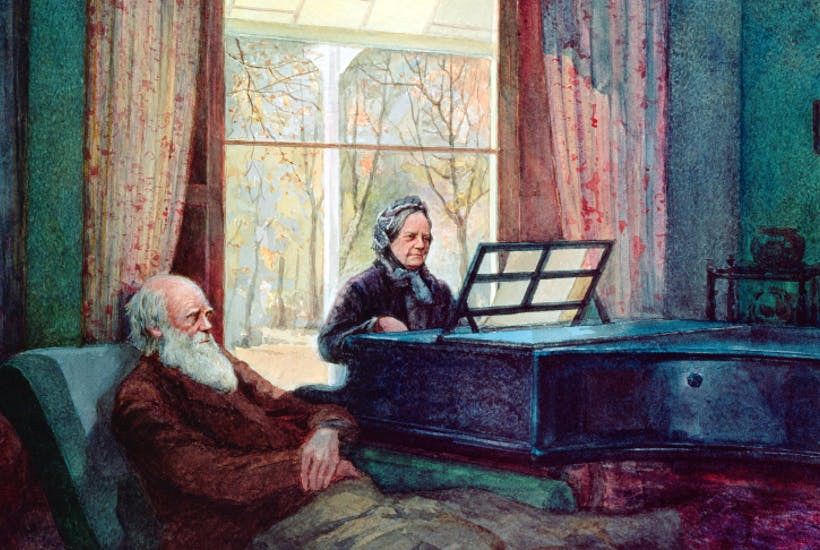

Both ended up inspiring each other in different ways. Emma, an accomplished pianist (she studied under Chopin), often serenaded Darwin with music. He, in turn, wrote about the evolution of musical talent as it relates to sexual selection.

Happily Ever After

The marriage was successful by any measure—the couple was still going strong after ten children. The stability of their relationship illustrates a surprising paradox in relationships: being irrational is sometimes the best way to be rational. Ultimately, Darwin combined both science and emotion, and offered the following pearl of wisdom:

In the long history of humankind (and animal kind, too) those who learned to collaborate and improvise most effectively have prevailed.”

Now that’s evolution.