“Women are machines for suffering.” – Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Two women left mentally unstable, two dead by suicide, others scarred for life. It’s an unsettling romantic track record for anyone – let alone one of the world’s most impactful artists.

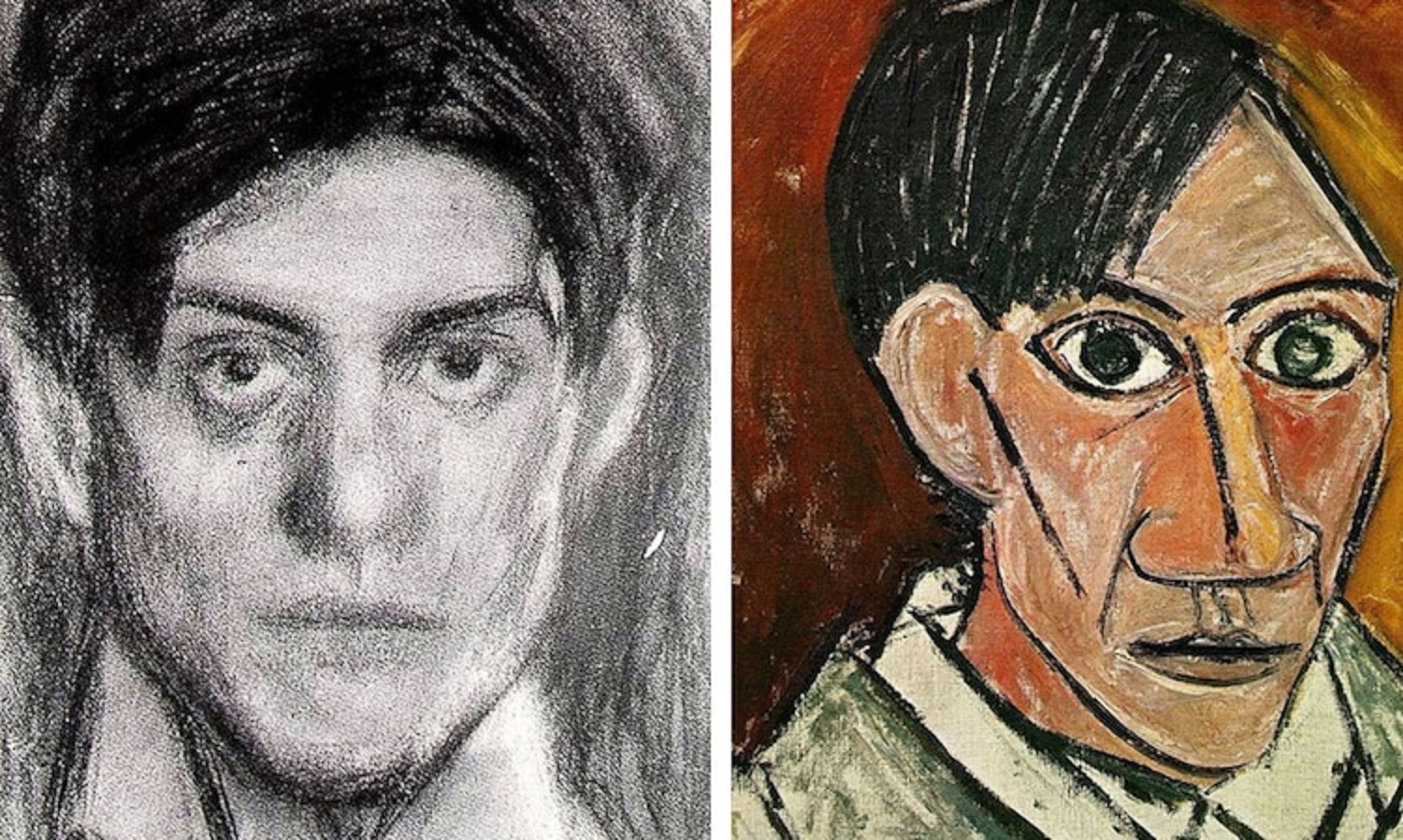

Pablo Picasso, heralded for his contributions to cubism and surrealism, was the unsung king of womanism. The man was seducing young women well into his 80s, all while producing some of the most influential artwork of the 20th century.

Apart from satisfying anyone’s appetite for sordid gossip, Picasso’s wildly energetic love life also sheds light on his transformations as an artist. His lovers had a remarkable influence over his work. Remember what he himself said: “I paint the way some people write their autobiography.”

His First Love

(1904-1913)

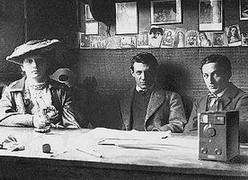

It was 1904, in the midst of Europe’s “Belle Epoque.“ One stormy night, Fernande Olivier, a Bohemian artist, was on her way home. She met 23 year-old Picasso, who blocked her path. She stopped. He held out a kitten. The rest was history.

It was 1904, in the midst of Europe’s “Belle Epoque.“ One stormy night, Fernande Olivier, a Bohemian artist, was on her way home. She met 23 year-old Picasso, who blocked her path. She stopped. He held out a kitten. The rest was history.

Both Picasso and Fernande were stormy lovers. In bouts of jealousy, Picasso often locked her up when he left the house. Despite being a Picasso-imposed recluse, when the purse strings grew tight, she was a good sport when he asked her to pawn her jewels. In the end, she was unfaithful to him, and to punish her, Picasso left her for her friend, Eva Gouel, (who then left him heartbroken when she died of tuberculosis in 1915.)

If you enjoyed Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, you have Fernande to thank. In addition to inspiring this famous work, Fernande was also the model for more than 60 portraits. She even played a role in Picasso’s transition from his Blue Period (1901-4) to his Rose Period (1904-6). During their relationship, he shifted from monochromatic, somber colors to cheerful orange and pink.

The First Wife

(1917-1935)

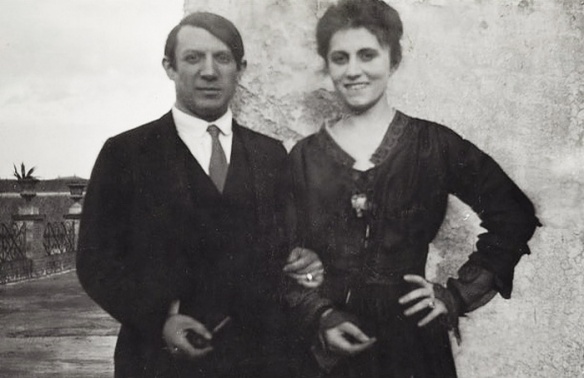

Olga Khokhlova was Picasso’s first wife, a Ukranian ballet dancer who didn’t share Picasso’s overwhelming love for his art. He waited 5 years before cheating on her with a 17 year-old.

During his relationship with Olga, Picasso’s depictions of women grew increasingly unflattering. For a glimpse of Picasso’s increasing hostility toward his wife, take a look at Three Dancers (1925). Note how the woman in the center appears to be undergoing crucifixion.

Likewise, Woman’s Head with Self-Portrait is a glimpse into Picasso’s own psyche and growing dissatisfaction with the constraints of matrimony. The “woman” flaunts a set of grotesque teeth and a wide, snapping mouth.

Did Olga take the hint? The two never divorced—Picasso was loath to relinquish half of his artwork to his wife, as would be mandated by law. But Picasso took a healthy dose of other lovers. Until her death in 1955, Olga kept herself busy: she stalked Picasso and his mistresses, wrote him hate mail, and went mad.

The Minor

(1927-1936)

“I had gone shopping to the Galeries Lafayette and Picasso saw me coming out of the Métro. He simply grabbed me by the arm and said, ‘’I’m Picasso! You and I are going to do great things together!’”

-Marie-Therese Walter

She was 17; he was a married 47 year-old. She was his greatest muse; he was the love of her life. On the back of one of Picasso’s poems, she wrote, “I love you and give you everything I have.”

Even though she was his intellectual inferior, Marie-Therese Walter provided Picasso some of the inspiration for works such as Vollard Suite. But hers was yet another tragic ending for Picasso’s spurned women; four years after Picasso’s death, she hanged herself in her garage.

The Mistress

(1936-1944)

While married to Olga and having an affair (and child) with Marie-Therese, Picasso found a new love interest. Dora Maar, a French photographer and painter, appears in Picasso’s famous Guernica.

While married to Olga and having an affair (and child) with Marie-Therese, Picasso found a new love interest. Dora Maar, a French photographer and painter, appears in Picasso’s famous Guernica.

The two met in a Parisian café. Picasso was impressed when Dora spread her fingers out on a table and quickly stabbed a knife in between the spaces in rapid succession. Unlike the movies, it didn’t go exactly as planned. She wounded herself and began bleeding. Picasso, ever the romantic, saved her bloodstained gloves for years.

Don’t think that Picasso’s wife, Olga, was happy with the affair. She often followed Picasso and Maar around. (Marie-Therese wasn’t thrilled, either.) Picasso, though, grew inspired by his jealous lovers, and used them as artistic playthings. He would paint Dora and Marie-Therese on the same couch—sometimes wearing each other’s clothes. Genius, or deranged?

Poor Dora didn’t fare well after Picasso lost interest, and she, too, suffered mental illness. Picasso didn’t help matters; instead, he flaunted his newest mistress in front of her—a 21-year old law student named Françoise Gilot. He asked Dora, “I’ve really discovered somebody, haven’t I?”

After the ill-fated relationship, Dora underwent intense psychoanalysis. She had this to say about her future life: “After Picasso, only God.”

The Fighter

(1944-1953)

“There’s nothing so similar to one poodle dog as another poodle dog, and that goes for women, too.”

– Picasso, to Francoise

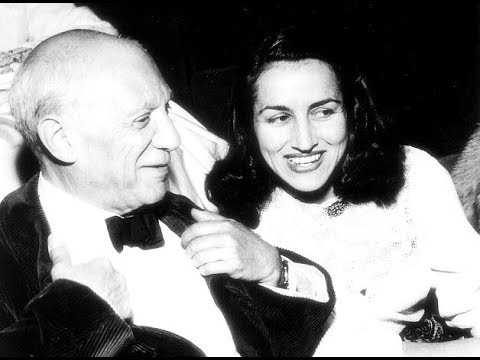

There’s a reason Hollywood made the movie about this lover – Francoise Gilot was the only one of Picasso’s women who spurned him. Strong-willed and unafraid, she wrote a best-selling book, Life with Picasso, in which she described him as “self-satisfied, indifferent to others, too convinced of his own worth” and “without indulgence to his family and entourage.”

There’s a reason Hollywood made the movie about this lover – Francoise Gilot was the only one of Picasso’s women who spurned him. Strong-willed and unafraid, she wrote a best-selling book, Life with Picasso, in which she described him as “self-satisfied, indifferent to others, too convinced of his own worth” and “without indulgence to his family and entourage.”

Watch the relationship unfold in the 1996 film, appropriately titled, Suiving Picasso (1996).

The Devoted

(1953-1973)

“Madame X,” as Picasso called Jacqueline Roque, was a married twenty-seven year-old when the two met. Though he was forty-five years older, he wooed her in style, drawing a giant dove in chalk on the wall of her home. The two remained together for twenty years, until Picasso’s death. He made 400 portraits of her.

“Madame X,” as Picasso called Jacqueline Roque, was a married twenty-seven year-old when the two met. Though he was forty-five years older, he wooed her in style, drawing a giant dove in chalk on the wall of her home. The two remained together for twenty years, until Picasso’s death. He made 400 portraits of her.

Jacqueline devoted herself to her husband, body and soul, regardless of the personal coast. When Picasso was buried, she slept on the snow over his grave. Years after Picasso’s death, she shot herself.

***

You’ve got to wonder: when did the man have time to paint?

We may never know why Picasso held such a dangerous allure for women. Physical lust is probably not the answer, unless Picasso was a foxy 80 year-old. Nor can his art alone be said to account for his magnetism—no one can have a real relationship with a canvas.

Perhaps the allure was simply the promise of something Picasso himself longed to achieve: immortality. Being the muse of a great artist meant being a part of the greatness he inspired. Many of Picasso’s most famous works scream Olga, Marie-Therese, Francoise. If the endurance of his art was in part a tribute to woman behind it, who wouldn’t be flattered?

Picasso himself may have summarized the matter best when he said, “Art is a lie that makes us realize the truth.” If we take this to be true, perhaps his greatest works, which have been lauded by the world of modern art, pale in comparison to what he felt for his real subjects. While Picasso’s women may have been mistreated and scorned, their relationships with him became “everlasting” by virtue of their enduring legacy in art.

[…] lines, bright colors and one weird prop. Jackson Pollack wore horizontally striped shirts. Picasso wore Panama hats. Salvador Dali had weird mustaches. Andy Warhol wore a big white wig. Artists […]