Have you ever been three hours late to your own wedding because you’re too busy planning an invasion of Italy? If so, you and Napoleon Bonaparte have something in common.

For one of the supposed greatest love stories in history, Napoleon and Joséphine’s marriage didn’t begin too well. It didn’t end well, either. And not a lot seemed to go right in between.

Napoleon

Napoleon began and ended life as an outcast. As a child, he was bullied in French schools for being scrawny, Corsican, and appallingly bad at public speaking. Napoleon had this to say of himself:

Always alone among men, I come home to dream by myself and to give myself over to all the forces of my melancholy.”

Perhaps it’s strange to imagine a weak side to the man was later nicknamed The Nightmare of Europe and the Armed Soldier of Democracy (and who would later appear in children’s stories as a carnivorous bogeyman). But Napoleon did have a heart—one that was surprisingly fragile. He knew the world as a place where “one had to learn to suffer and not let others see it.”

Joséphine

Joséphine, meanwhile, had a different set of problems. Married at 16 to 19 year-old Alexandre Vicomte de Beauharnais, she gave birth to his children and then was promptly deserted by him (he took a mistress and set up camp in Martinique.)

The marriage came to a shaky reconciliation years later, but it didn’t last long: Alexandre was arrested during the French Revolution and swiftly guillotined in 1794. Joséphine awaited her own execution in prison, but was released when Robespierre beat her to the guillotine. The Reign of Terror ended.

The marriage came to a shaky reconciliation years later, but it didn’t last long: Alexandre was arrested during the French Revolution and swiftly guillotined in 1794. Joséphine awaited her own execution in prison, but was released when Robespierre beat her to the guillotine. The Reign of Terror ended.

Time in prison wasn’t a total loss for Joséphine—rumor has it that it was in the Carmes prison where she met General Hoche, who she assumed would leave his wife for her.

The Romance

Napoleon met Joséphine 1795. He was a brigadier general en route to becoming one of the world’s greatest military commanders; she was six years his senior, the mother of two children, and the instant love of his life.

In Joséphine, Napoleon finally seemed to find an outlet for emotions he may have previously repressed. His letters documented his increasing passion:

I awake full of you. Your image and memory of last night’s intoxicating pleasures has left no rest to my senses.”

Joséphine, meanwhile, thought Napoleon was “silent and awkward with women,” and wasn’t thrilled about the prospect of marriage. She had another lover at the time – Paul Barras, who gladly handed her off to Napoléon because she was becoming too expensive.

The Wedding

The wedding day wasn’t a rollicking success. The groom was late, the bride didn’t seem to love the husband, and both lied about their ages on the marriage certificate.

The wedding night was worse. Napoléon came to bed only to discover Joséphine’s poodle happily lying in his spot. Joséphine refused to make the dog move, insisting that the pooch always slept on her bed.

Napoléon tried to consummate the marriage, and the dog bit him on the shin.

The Marriage

There wasn’t time for things to improve dramatically after the wedding night. Two days into their marriage, Napoleon left to invade Italy, and then Egypt.

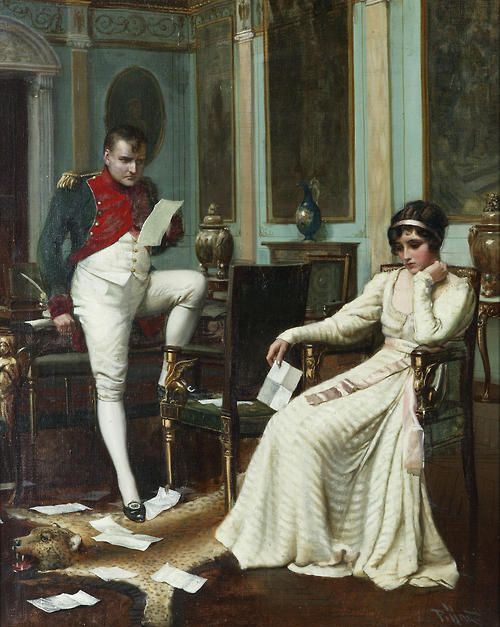

Arguably, the real love story between the newlyweds didn’t happen in person at all. Rather, it occurred in Napoleon’s devoted letters to his apathetic bride.

April 3, 1796

… to die not loved by you, to die without knowing, would be the torment of Hell, the living image of utter desolation. I feel I am suffocating. My one companion, you whom fate has destined to travel the sorry road of life beside me, the day I lose your heart will be the day Nature loses warmth and life for me.”

Poignant words—and unsettlingly prophetic. During that same year, Joséphine began an affair with Hippolyte Charles. When rumors of the affair reached Napoleon, he fell into a grave denial. His passion grew more and more desperate, and his letters teetered on the verge of Too Much Information:

November 21, 1796

… I cannot wait to give you proofs of my ardent love… How happy I would be if I could assist you at your undressing, the little firm white breast, the adorable face, the hair tied up in a scarf a la creole…Kisses on your mouth, your eyes, your breast, everywhere, everywhere.”

The Affairs

Six days after writing this letter, Napoléon visited Joséphine’s apartment in Milan. It was empty. He waited nine days for her, but she’d gone to Genoa, presumably with her lover. Napoléon, who could no longer deny the affair, wrote her the following:

I don’t love you anymore; on the contrary, I detest you. You are a vile, mean, beastly slut. You don’t write to me at all; you don’t love your husband; you know how happy your letters make him, and you don’t write him six lines of nonsense…”

At this point, you might be wondering: where are Joséphine’s letters to Napoléon?

Few of them exist. Either they haven’t survived two hundred years, or she simply didn’t write any. What has survived is a letter Joséphine wrote to her lover, Hippolyte, in 1798:

Hippolyte, I’ll kill myself. Yes! I want to end a life which from now on can only be burdensome to me if it cannot be consecrated to you.”

The Reversal

Joséphine’s affair was decidedly tragic for her husband. Disillusioned and increasingly embittered, Napoléon had this to say on the subject:

I need to be alone. I am tired of grandeur; all my feelings have dried up. I no longer care about my glory. At twenty-nine I have exhausted everything.”

Remarkably, Napoleon took Joséphine back—his ardor (if not trust) largely intact.

For a general whose military might depended upon the loyalty of his army, it is somewhat startling that Napoleon forgave the betrayal of the one person who was closest to his heart. His calculating military mind managed to excuse his most dramatic miscalculation.

Napoleon did, however, take other mistresses, and flaunted them in front of his wife’s face. Pauline Bellisle Foures, with whom Napoleon began an affair in 1798, became known as “Napoleon’s Cleopatra.”

This is where the pseudo-Greek tragedy begins: as Napoléon became increasingly adulterous, Joséphine became more and more faithful. She learned to feel the same jealousy and desperation that she herself once inspired in her husband. Her affection for her husband gradually equalled his initial devotion for her—only years too late.

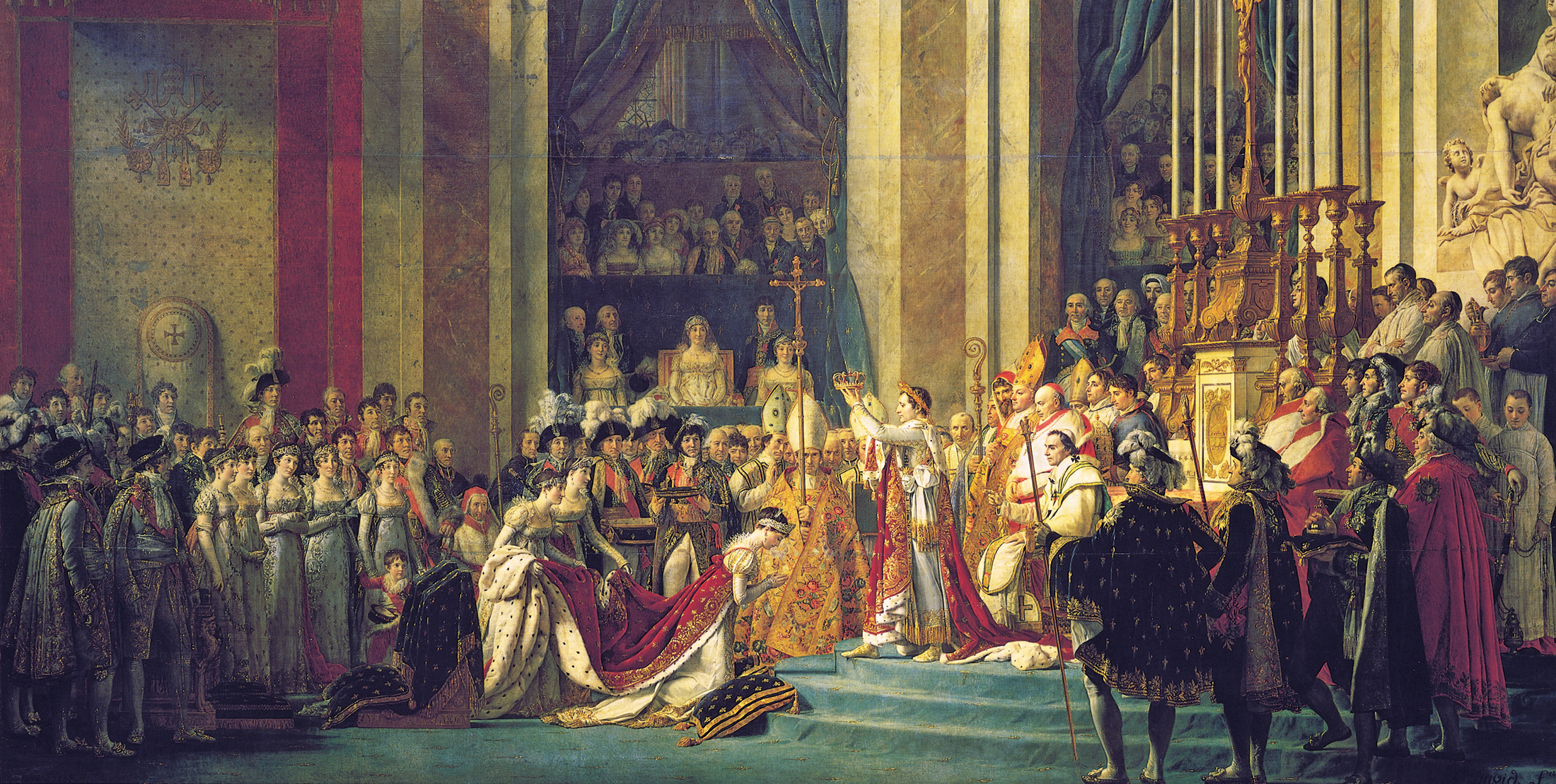

And so, while she gained the title of Empress, she lost her real power: her unequivocal hold over the Emperor’s heart.

The Split

Napoleon divorced Joséphine on January 10, 1810. Political concerns drove his choice: Joséphine was not able to provide him with a child (it is speculated that the stress of prison had taken its toll on her body), and Napoleon wanted an heir. He also hungered for a connection to the European royal line, which would legitimize France’s new political regime.

He found both fertility and nobility in Marie Louise, the Archduchess of Austria, whom he unromantically called a “womb.” He married her on March 12, 1810—by proxy.

What had happened to the hopeless romantic who had penned amorous letters to his lover? Had Napoleon allowed his quest for political control to overcome his desire to be loved? After all, Napoleon divorced a woman for whom he still felt a deep and abiding affection.

Perhaps Napoleon explained his motives himself in his famous phrase: “Glory is fleeting, but Obscurity is forever.” Certainly, the “glory” he referenced it easy to define: Napoleon sought power, military might, and a lasting legacy. But the question of “obscurity” is more interesting. Was it political obscurity that Napoleon feared—or the obscurity that erupts when one feels insufficiently loved?

The Legacy

The relationship between Napoleon and Joséphine illustrates an unflinchingly human portrait of a man who is usually remembered for his military genius and unparalleled ambition. His heartbreak speaks to everyone because it has been felt by everyone—from every walk of life. The Great Napoleon, victimized by unrequited love, may have had something in common with even the lowliest of his subjects.

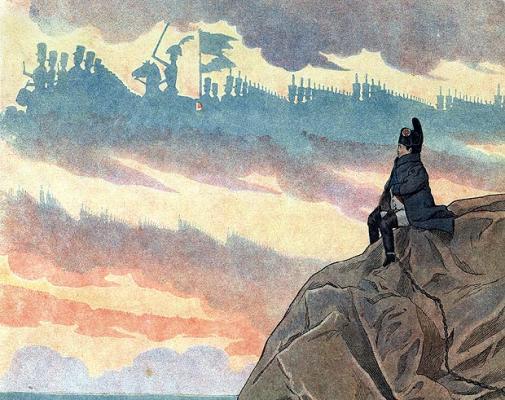

It is also worth noting the change that occurred in Napoleon as his relationship with Joséphine evolved. He transformed from a boyishly excited young lover to a hardened general.

While it would be extrapolating too far to insist that Napoleon’s European campaign stemmed from the frustration in his love life, his letters do illustrate the relationship between love, disappointment, and power:

I am not a man like others and moral laws or the laws that govern conventional behavior do not apply to me. My mistresses do not in the least engage my feelings. Power is my mistress.”

We all know how Napoleon’s power binge ended. He was exiled to Saint Helena, where only his legacy was left to kept him company.

Napoleon’s stamp upon history was, admittedly, impressive—he redefined military strategy, modernized an entire continent, and developed a code of law that has influenced the entire world. But perhaps his greatest legacy has nothing to do with his political or military success. On his deathbed, Napoleon left behind a simple lesson that is applicable to everyone, emperor or civilian. You can conquer a vast empire, but ultimately, what you cherish is the memory of what you loved the most.

His last words speak for themselves:

France, the Army, the Head of the Army, Joséphine.

Read more : Nietzsche’s Secret Guide to Love